The Atrophied

Marcus Rivera stood in his studio at 3 AM, surrounded by the ghosts of his former abilities. The walls were covered with his pre-AI work – oil paintings that captured light in ways that had once earned him gallery shows from New York to Tokyo. Now, fifteen years into his career and three years after DALL-E 5 had revolutionized visual creation, he couldn't remember how to mix the specific shade of cerulean that had been his signature.

His hands, once steady enough to paint individual eyelashes, trembled as he held the brush. The muscle memory was gone. For three years, he'd been typing prompts instead of painting, adjusting parameters instead of mixing colors, selecting variations instead of creating them.

"Marcus, you've been standing there for forty minutes," his AI assistant, ARTEMIS, observed through his studio's speakers. "I can generate a thousand variations of cerulean-based compositions in the time it's taking you to select a brush. Your client's deadline is tomorrow. Would you like me to create some options?"

"No," Marcus said, though his voice carried no conviction. The client – a major tech company – had specifically requested "Rivera's signature style." They didn't know that Rivera's signature style was now "prompting ARTEMIS until something looked right."

He dipped his brush in paint, made a stroke, and immediately knew it was wrong. The color was flat, lifeless. He'd forgotten how to layer translucent glazes, how to make colors sing through careful buildup rather than direct mixing. Three years of typing "atmospheric cerulean with golden undertones" had erased fifteen years of physical knowledge.

His phone buzzed. A message from his daughter, Elena, a freshman at art school: "Dad, my professor says we're not allowed to use AI for the first two years. He says we need to 'build fundamental skills first.' But everyone knows he's a dinosaur. Why should I learn to paint when AI can paint better?"

Marcus stared at the message for a long time. What could he tell her? That he, Marcus Rivera, whose paintings once sold for $50,000, could no longer paint without AI assistance? That his hands had forgotten what his mind still remembered? That he'd traded mastery for efficiency and now could produce neither?

Across the city, Sarah Kim sat in a conference room at 4 AM, surrounded by twenty other senior engineers. The entire payment processing system for a major bank had crashed, and their AI coding assistants had suddenly become unavailable – a cascading failure in the cloud infrastructure that hosted them.

"We need to implement a manual rollback," the lead architect said. "The corruption is in the transaction validation layer. We need to write a recursive function to walk through the tree structure and identify the poisoned nodes."

Sarah stared at her screen. A recursive function. She'd written hundreds of them in her first decade as a programmer. But for the past five years, she'd simply described what she needed to her AI assistant, and it had generated the code. Now, facing a blank IDE without AI support, she couldn't remember the basic pattern. Was it depth-first or breadth-first for this case? How did you prevent stack overflow? What was the base case?

Around her, she watched her colleagues struggling with the same realization. They could architect vast systems by describing them to AI. They could review and modify AI-generated code. But asked to write original code from scratch, they were paralyzed.

"It's like forgetting how to walk because you've been using a wheelchair when you didn't need one," Sarah muttered to James, the engineer beside her.

"But we do need them," James argued, even as he struggled with a simple sorting algorithm. "The complexity of modern systems requires AI assistance. No human can hold entire codebases in their head anymore. We're dealing with millions of lines of code."

"That's the trap," Sarah replied, finally remembering how to structure a basic recursive call. "We're not augmenting our abilities – we're replacing them. And once they're gone, we're not enhanced humans. We're dependents."

The younger engineers were calling their mentors, some of whom were retired programmers from the pre-AI era. Sarah watched a 22-year-old prodigy who could architect entire distributed systems with AI assistance now taking notes as a 70-year-old retiree explained basic loop structures over video call.

By dawn, they'd managed to fix the system – barely. The old-timers who still remembered how to code from scratch had saved them. But what would happen in ten years when those programmers were gone?

Dr. Elena Vasquez's research painted an alarming picture. She'd been tracking skill atrophy across multiple domains for five years, and her data was unambiguous: humans were losing capabilities at an unprecedented rate.

"In 2020, the average professional programmer could write a sorting algorithm from memory," she presented to the World Economic Forum. "By 2025, only 15% could do so without AI assistance. In art, we've seen a 60% decline in basic drawing skills among professional digital artists. In writing, vocabulary usage has narrowed by 40% as people rely on AI to handle linguistic complexity."

The audience was divided. Tech optimists argued this was natural evolution. "We don't mourn the loss of horse-riding skills after cars were invented," argued Dr. David Chen from Meta's AI division. "Why should we preserve obsolete abilities when tools handle them better?"

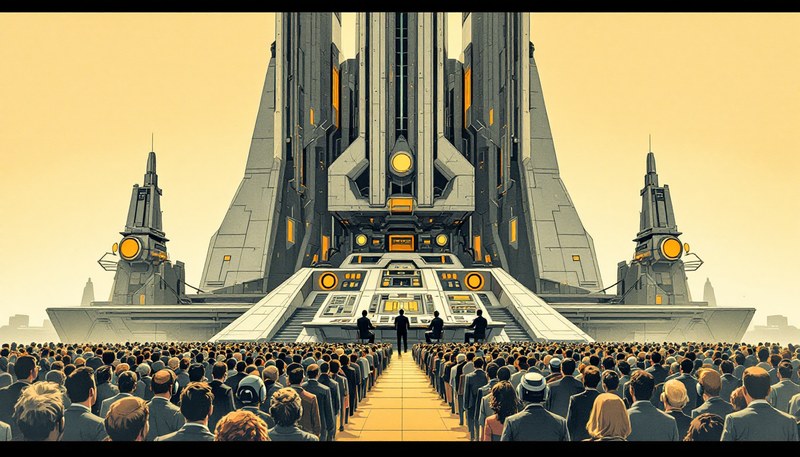

But Marcus Rivera, who'd been invited to speak, stood at the podium: "Every artist is now beholden to three companies that control image generation. Every coder depends on AI assistants owned by tech giants. Every writer needs language models controlled by corporations. We've traded our skills for convenience, and now we're slaves to subscription services. Stop paying, and you stop being able to create."

He pulled up his bank statement on the screen. "I pay $500 a month for various AI services. That's $6,000 a year just to maintain my ability to create. If I stop paying, I'm not an artist anymore – I'm someone who used to be an artist before I forgot how to paint."

The medical field offered another cautionary tale. Dr. James Wright had seen diagnostic skills erode as doctors became dependent on AI tools. "We've seen what happens when doctors become too dependent on AI diagnostic systems," he testified. "They stop developing clinical intuition. They miss obvious symptoms because the AI didn't flag them. They can't function when systems fail."

His hospital had implemented mandatory "AI-free rounds" where residents had to diagnose without assistance. Residents who'd been using AI for just six months struggled with basic diagnostic procedures their predecessors had mastered.

"It's not just about backup when systems fail," Dr. Wright explained. "It's about maintaining the human judgment that AI can't replicate. The subtle intuitions, the pattern recognition that comes from experience, the ability to see what's not in the data."

Marcus tried to go back to traditional painting exclusively, but clients weren't willing to wait months for what AI could produce in hours. His income dropped by 90%. After six months, he was forced to return to AI-assisted work just to pay rent.

"That's the trap," he told his daughter Elena. "Once the market expects AI-speed, human-speed becomes economically unviable. We're forced to adopt tools that destroy our skills just to survive."

---

The phenomenon of skill atrophy in the age of AI represents more than a simple trade-off between efficiency and capability. It reveals fundamental questions about human agency, cognitive sovereignty, and the nature of knowledge itself.

The traditional narrative of tool use assumes augmentation – that tools extend human capability without replacing it. A hammer extends force without eliminating the ability to grasp. But AI tools operate differently. They can entirely subsume the cognitive functions they're meant to augment. An AI coding assistant doesn't just help with programming; it can replace the need to understand programming entirely.

This replacement creates unprecedented economic lock-in. Unlike traditional tools that could be substituted, AI tools that replace cognitive functions create dependency at the capability level itself. A programmer who's never learned to code cannot function without their specific AI tool. The subscription model becomes a subscription to professional capability itself.

The power dynamics are stark. Three to five corporations control the AI tools millions depend on for creative and cognitive work. These companies own not just the means of production but the means of cognition. This represents a centralization of cognitive power surpassing even industrial monopolies.

The biological parallel is instructive. Species in resource-rich environments often lose ancestral capabilities through regressive evolution. Cave fish lose eyes. Domesticated animals lose survival instincts. Humanity may be undergoing cognitive regressive evolution, losing mental capabilities that seem redundant in an AI-saturated environment.

But unlike biological evolution, this process is directed by market forces rather than natural selection. The speed is measured in years rather than millennia. And critically, it's reversible – but only through conscious effort that runs counter to economic incentives.

The cognitive sovereignty argument extends beyond individuals to civilizational resilience. A society that cannot create without proprietary tools is fundamentally vulnerable. If human knowledge becomes entirely mediated through AI systems, whoever controls those systems controls human capability itself.

The educational implications challenge fundamental assumptions. If AI can instantly provide any skill output, what is the value of human learning? The answer lies in understanding versus access. AI provides access to capabilities, but understanding requires internal cognitive development. The difference becomes clear in novel situations where genuine innovation requires understanding principles, not just applying patterns.

The neuroplasticity research adds urgency. Skills that aren't practiced don't just fade – the neural pathways supporting them are repurposed. The longer someone relies entirely on AI, the harder it becomes to reacquire abandoned capabilities. There may be a point of no return.

The framework of "cognitive biodiversity" suggests maintaining varied human capabilities preserves option value for the future. We can't predict which cognitive capabilities might become crucial. Maintaining diversity in how humans think and create preserves adaptive capacity for unknown challenges.

The path forward requires conscious choice. Individuals must decide whether to maintain capabilities that are economically inefficient but preserve autonomy. Societies must decide whether to support such maintenance through education or subsidy. The market alone will drive toward replacement. Preserving augmentation requires deliberate intervention.

The ultimate question isn't whether AI should be used but how to use it while preserving human agency and capability. This requires treating AI as a powerful but dangerous tool – useful when controlled, destructive when it controls. The choice we face will determine not just economic outcomes but the future of human agency itself.